The draw and pitfalls of intuition

It is hard to resist trusting our intuition — after all, thousands of years of evolution have trained us to rely on it. While intuition often works well, its limitations become especially clear in organizational leadership.

We tend to favor information that confirms what we already believe, overestimate the likelihood of memorable events and give too much weight to the first piece of information we receive. In personal life, these errors can be embarrassing or costly. In leadership, the stakes are much higher: over-reliance on instinct can misdirect entire organizations and impact employees, stakeholders and long-term strategy.

Why do even intelligent, experienced leaders fall into this trap? Partly because it feels natural and comforting to trust one’s instincts. Another factor is overconfidence: accomplished leaders often assume that their knowledge and past successes are enough to guide every decision. But no matter how skilled a professional is, cognitive biases — subconscious mental shortcuts our brains use to process information — can lead to serious errors.

Even highly competent professionals can make surprisingly poor decisions if they rely too heavily on intuition alone. When those professionals are organizational leaders, the consequences can be significant.

Making data work

W. Edwards Deming, a pioneer in statistical quality control, famously said, “In God we trust; all others must bring data.” Objective evidence is the clearest way to counter biased intuition, but having data is one thing; turning it into meaningful insight is another.

Leaders often face cognitive dissonance: the mental discomfort that comes when information contradicts their beliefs. It can feel easier to reject evidence than to question long-held assumptions, which is why even experienced leaders sometimes ignore data and rely on instinct.

Evidence-based management provides a solution. By using structured, fact-driven processes, organizations can base decisions on objective information rather than intuition alone. Modeled after evidence-based medical practice, this approach helps leaders focus on what the data actually shows so they can make more rational, informed choices.

Let evidence speak for itself

Evidence-driven decision-making is compelling, but applying it in practice can be challenging. One of the first questions is: what counts as evidence?

In management, the term “anecdotal evidence” is often used to support decisions. But anecdotes — stories of individual experiences or events — are not systematically verifiable and may not be reliable. True evidence is objective information that can justify or support conclusions. In other words, something can be either an anecdote or evidence, but rarely both.

For leaders, distinguishing between story and evidence is critical. Only reliable, verifiable information can help counter biased intuition and guide better decisions.

Dueling conceptions of the idea of evidence

What counts as evidence can depend on perspective. The dictionary defines evidence as facts or organized information that supports beliefs or conclusions. While the “facts” part is usually clear, “organized information” can mean different things in different contexts.

In science, evidence must be objectively verifiable, leaving personal beliefs or intuitions out. In some social or psychological contexts, evidence can be defined more loosely to include perceptions or beliefs — but in organizational decision-making, blurring the line between objective facts and subjective intuition is counterproductive.

Objective evidence is essential for countering biased intuition and preventing dysfunctional dynamics like groupthink or the “highest-paid person’s opinion” effect (HiPPO). While the value of objective evidence is clear, identifying and using it effectively can be challenging.

Too many inputs, not enough guidance

Even when leaders focus only on objective evidence, the sheer volume of information can be overwhelming. Too many data points, especially if they conflict, can confuse rather than clarify, leaving decision-makers frustrated. Organizations often describe themselves as “data rich but information poor,” and information overload can push leaders back toward relying on intuition.

To be useful, evidence must be synthesized into clear, decision-guiding insights. This requires a structured process: grouping similar inputs, reconciling divergent signals and applying a weighting system to ensure the most reliable information carries the most influence. Only then can objective evidence guide rational, well-informed decisions.

Making sense of conflicting evidence

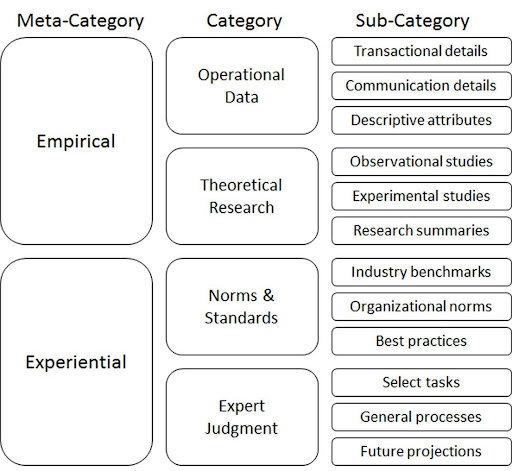

In my book Evidence-Based Decision-Making, I outline a framework for turning diverse evidence into actionable insights: the empirical and experiential evidence (3E) framework. The idea is to take the variety of decision-related information and systematically synthesize it into clear, decision-guiding knowledge.

The framework begins by organizing evidence into two broad categories: empirical and experiential. Empirical evidence includes recorded events and objective data, such as operational metrics or research findings. Experiential evidence captures objectified learnings from experience, such as pooled expert opinions or recognized best practices. Each of these categories can be further subdivided into more specific types of evidence, creating a structured, organized system.

The framework begins by organizing evidence into two broad categories: empirical and experiential. Empirical evidence includes recorded events and objective data, such as operational metrics or research findings. Experiential evidence captures objectified learnings from experience, such as pooled expert opinions or recognized best practices. Each of these categories can be further subdivided into more specific types of evidence, creating a structured, organized system.

Once organized, evidence is synthesized step by step. Data points within each subcategory are summarized, category-level insights are pooled and an explicit weighting system ensures the most reliable information carries the greatest influence. This structured process condenses diverse, sometimes conflicting inputs into unambiguous knowledge that can guide decisions.

Even after this careful synthesis, one challenge remains: overcoming the natural tendency of leaders to trust their instincts over evidence.

Overcoming the ‘gut feel’ inertia

Experienced leaders often rely on their knowledge and past experience as a “smell test”: does new information match what they already believe? If not, why trust it over years of expertise?

The problem is that intuition can mislead us. Our reasoning is shaped by subconscious cognitive processes, mental shortcuts and the constant influx of stimuli, which can warp judgment without our awareness. Even the most skilled professionals are susceptible to these hidden biases.

Properly curated objective evidence can counterbalance biased intuition. To make better decisions, leaders should follow a two-part strategy:

- Awareness: Understand the pitfalls of relying solely on intuition. Recognize how biases can influence judgment, even subconsciously.

- Refocusing: Build a habit of checking intuition against objective evidence, rather than letting instinct override the facts.

By consciously integrating evidence into decision-making, leaders can reduce the risks of unchecked “gut feel” and make more reliable, rational choices.

Leading with facts

Evidence-based management doesn’t replace intuition — it balances it. Leaders who combine experience with rigorously analyzed information are better equipped to navigate complexity, reduce risk and make informed, confident decisions.

The goal is to cultivate a habit of checking intuition against objective evidence rather than letting instinct dictate judgment. By grounding decisions in reliable, verifiable information, leaders can improve outcomes, foster trust within their teams and create a culture of thoughtful, data-informed management.